Rhetoric of Health & Medicine

Vol. 1, Nos. 1–2, pp. 193–212

A Dialogue with Medical Interpreters About Rhetoric, Culture, and Language

Laura Gonzales and Rachel Bloom-Pojar

Featured Contributors: Griselda Perez, Alex Leger, Carla Sanchez, Rawa Rafaiel, Apoul Anyijong, Jaylyn Yff, Mary Raab, Betty Mulac, and John Brown

Through conversations with medical interpreters who work in Grand Rapids, Michigan, this dialogue piece illustrates multiple ways that medical interpretation can be further considered as a method and practice within the rhetoric of health and medicine (RHM). By sharing specific methodological frameworks for researching medical interpretation, the authors introduce possibilities for how RHM research can continue to engage in work that extends beyond English-dominant communication.

KEYWORDS: linguistic diversity, advocacy, interpretation, multilingual, translation space, translation moment

Introduction

In 2016, the Center for Immigration Studies (2016) reported that nearly 65 million U.S. residents speak a language other than English at home. This number has increased by 1.5 million since 2014, and has risen by 5.2 million since 2010. Of the individuals who speak languages other than English at home, 40% reported to the Census Bureau in 2015 that they speak English “less than very well” (Center, 2016, n.p.) As this data suggests, caring for individuals who identify with heritage languages other than English or who identify as having Limited English Proficiency (LEP)1 is only becoming increasingly critical, both in and outside of the United States. Language accessibility, or the availability of usable information in languages other than English, is an issue of growing importance, particularly in high-stakes environments like healthcare (St. Germaine-McNaniel, 2010; St.Amant, 2017).

Scholars in technical communication, the rhetoric of health and medicine (RHM), and related fields continue to work closely with healthcare practitioners to develop strategies that can improve language accessibility in healthcare contexts (Agboka, 2013; Batova, 2010; Ding, 2014; Rose et al., 2017). For example, researchers continue to point to the need for translating and localizing (Sun, 2012) tools and technologies for linguistically and ethnically diverse patients, while also addressing accessibility concerns for patients with various (dis)abilities. Scholars have presented frameworks such as “patient experience design (PXD)” (Meloncon, 2017), “international patient experience design (I-PXD)” (St.Amant, 2017), and “community-based user-experience design” (Rose et al., 2017) to help practitioners facilitate multilingual and cross-cultural healthcare interactions. Alongside this work, researchers like Godwin Agboka (2013) continue to advocate for the need to protect and value the expertise and experiences of linguistically and ethnically diverse users, particularly when working within “unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites” (p. 298). Rather than conducting research about marginalized communities (e.g., communities of color who identify with heritage languages other than English), scholars like Agboka (2013) and Rose et al. (2017) continue to point to the need to conduct research with and for the communities that we seek to support as rhetoricians interested in issues of access, accessibility, and equity.

Drawing on the increasing impetus for examining and improving healthcare resources in languages other than English, this dialogue piece seeks to illustrate the rich rhetorical work that takes place as health-related information moves across languages in medical settings, particularly through the rhetorical labor of medical interpreters. As RHM continues focusing on issues of linguistic and cultural difference, we argue that it’s important for our field to consider the work being done to make health-related information accessible to people whose heritage languages include more than English, making space to highlight these multilingual discourses more directly in RHM scholarship, pedagogy, and practice. Leveraging the dialogue genre established by this journal, we seek to provide a space for medical interpreters to discuss the work that they do for their communities in their own words. Thus, this dialogue piece is an attempt to listen to and learn from medical language interpreters as they work to make healthcare more useful and ethical to and for marginalized communities.

Following the genre of a dialogue piece as described on the Rhetoric of Health & Medicine (RHM) journal website, this piece is crafted as a conversation between RHM researchers, Laura and Rachel, and several medical interpreters, who co-constructed the information and ideas of this entry. We weave the presentation of our own theoretical frameworks with quotes and examples provided by healthcare practitioners, in an attempt to center the perspectives and experiences of “nonacademic stakeholders” (RHM Author Guidelines). At times, we provide detailed analyses of the observations shared by medical interpreters. In other instances, however, we also aim for the medical interpreters’ quotes to stand on their own. In the sections that follow, we will first elaborate on the impetus for and the structure of this piece. Next, we introduce the theoretical concepts that ground our approach to working with medical interpreters, sharing our concepts of “translation spaces” and “translation moments” as method/ologies that can further inform how RHM advocates for the value of linguistic diversity in healthcare interactions. Then we discuss our method for gathering insights about RHM from medical interpreters who provide language accessibility for their communities. Finally, drawing on the themes that emerged from our interviews and focus groups with medical interpreters, we present further implications for RHM researchers aiming to engage in research and practice with linguistically diverse communities.

Our Goals for RHM

I became an interpreter because I saw the need in the community.… Growing up, we had to learn both languages. So, back then, there was no such thing as an interpreter. So, we had to interpret for our parents. Everywhere we went, one of us would have to come along to help interpret for them. It could be the grocery store or at the clinic or at the hospital, at an appointment … one of us always had to come along to interpret because there was no interpreters back then. So … when I would come to the hospital and see the interpreters, I was amazed. I was like, ‘I wish I could become an interpreter one day,’ and I got the opportunity one day. (Gris, Medical Interpreter, Hispanic Center of Western Michigan)

As a field, RHM seeks to highlight how language and other forms of communication shape how people experience health and healthcare, whether that is in an examination room, in the media, and/or in their communities (Segal, 2005; Ding, 2014; Meloncon & Scott, 2018). In many ways, RHM researchers have historically focused on issues of access (e.g., access to health literacy and scientific information) and power (e.g., relationships between providers and patients, dynamics between professional and public discourses related to health and medicine) in their research. This work highlights the systems of privilege and oppression that are frequently at play in healthcare interactions. As RHM launches its inaugural issue, we want to extend the field’s tradition of highlighting often overlooked rhetorical practices that take place during health-related interactions, bringing to the forefront how issues of language, culture, and difference shape how patients and providers discuss and understand concepts of health and illness. Specifically, we seek to start conversations within the pages of RHM that address directly issues of language and culture, acknowledging the fact that contemporary conversations and practices in health and medicine inherently happen in multiple languages across multiple communities, where a standard discourse is neither practiced nor desired.

As researchers, we are interested in the rhetorical work that healthcare practitioners and patients navigate in their everyday practices as they negotiate meaning across linguistic and cultural boundaries. Because RHM is both a (multi)disciplinary area of research and an avenue for studying professional practices, it is important for us to ground any discussion of specific RHM activities in the experiences of both researchers and practitioners. Thus, our goal for this dialogue is to describe the intellectual and professional work of medical interpreters, and also to make space in the field of RHM for the rich histories and experiences of the individuals who use multilingual rhetoric to provide access to healthcare in their communities. To this end, in the section that follows, we first define medical interpretation and then present two concepts—translation spaces and translation moments—as potential frameworks and approaches for studying language diversity in RHM.

Theorizing Medical Interpretation

As interpreters or translators, you are a communicator. Being part of a job, communication is typically one of your skills. So being able to play with words and language to make it make sense can come easy to some interpreters. (Jaylyn, Medical Interpreter, Hispanic Center of Western Michigan)

We’re all about breaking down barriers and I think in our own small way, translators and interpreters really do try to help make the world a better place and bring people closer together. If you can gain someone’s trust and you can get them to see you as a human being, not just as a label, you really have done something very significant. (Mary, Medical Interpreter, Hispanic Center of Western Michigan)

Medical interpreters are individuals trained to facilitate conversations between healthcare providers and patients who speak different languages. Due to its focus on facilitating communication between various stakeholders in health-related interactions, medical interpretation highlights several rhetorical aspects central to the field of RHM. In many ways, medical interpretation is RHM in practice—a profession that hinges on the successful adaptation of ideas and concepts across audiences and contexts. As medical interpreters translate information across languages for patients and healthcare providers, they have to both translate and localize health-related information using rhetorical strategies and resources to make information accessible to a wide range of audiences.

In our previous projects with medical interpreters, we developed two concepts that helped us identify and study the rhetorical work that takes place during multilingual healthcare interactions. In a previous project with Spanish-English medical interpretation in the Dominican Republic, Rachel developed the concept of translation spaces as a way to describe any space that requires some type of translation work across different forms of meaning making through various modes, languages, and discourses (Bloom-Pojar, 2018, p. 25). This perspective of translation also integrates textual spaces, as written and spoken discourses are mediated and texts are transformed through conversation. Therefore, translation spaces serve as contexts where language users negotiate between different modes (e.g., spoken-written, verbal-nonverbal), languages (e.g., English-Spanish, Spanish-Spanish), and institutional and communal discourses (e.g., professional and lay terminology).

Within translation spaces, translation moments are what Laura defines as decision-making points in the translation process, or instances in time when individuals pause to make a decision about how to transform a specific word or phrase from one language to another (Gonzales, 2018, p. 22). Translation moments are the instances where multilingual communicators pause to ask, “Should I use this word, or that one? Is this phrase better here, or should I use that other phrase? What ‘sounds right’ in this specific translation?” During translation moments, multilingual communicators draw upon their lived experiences and cultural knowledge to enact rhetorical strategies that help them accurately transform information across languages for a specific audience at a specific moment in time.

Because language is fluid, “accurate” or “precise” translations of specific words or phrases are constantly shifting. What is determined to be a correct translation of a specific word in one context may completely shift when speaking to a different community. For this reason, multilingual communicators use translation moments to rhetorically contextualize language for specific audiences in specific contexts. This is especially the case during medical interpretations, where interpreters have to navigate medical terminology across different specializations and medical units (e.g., cardiology, pediatrics) while simultaneously navigating the various cultural and linguistic differences in the patients and healthcare providers that they engage with during each interpretation session.

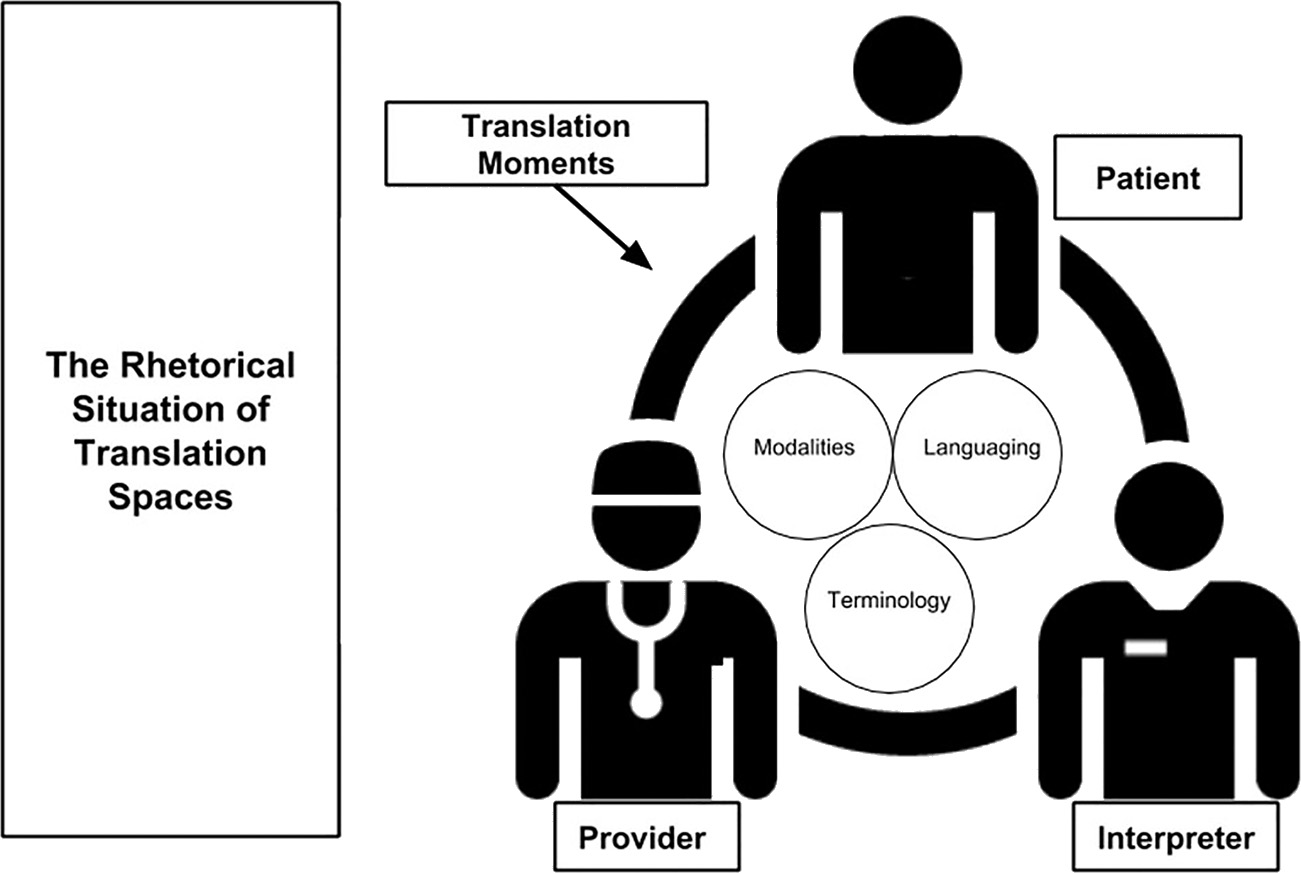

Figure 1 provides a visualization of the relationships between medical interpretation, translation spaces, and translation moments.

Our concepts of translation spaces and translation moments can be useful approaches to studying medical interpretation in RHM. In the forthcoming collection, The Rhetoric of Health and Medicine as/is: Theories and Concepts for an Emerging Field, we argue that researchers in RHM can trace translation moments and translation spaces that are established across healthcare interactions, noting how healthcare practitioners can further recognize the rhetorical work that linguistically diverse patients are engaging in as they make sense of information in English.

Figure 1. Medical interpretation, translation spaces, and translation moments

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between translation spaces and translation moments when an interpreter translates information between a patient and a health practitioner (e.g., doctor). Within this translation space, translation moments come up as the interpreter navigates any difficulty in transforming information across languages. During translation moments, interpreters use various rhetorical strategies, including modalities like gesturing, and they use digital technologies, language practices, and terminology to facilitate communication between the patient and the health practitioner.

After developing and presenting translation moments and translation spaces in previous projects as frameworks for studying language diversity in RHM, we also wanted to provide a space for medical interpreters to describe their work in their own words. For this reason, we recently interviewed and held focus groups with medical interpreters at the Hispanic Center of Western Michigan, using these conversations as a way to further illustrate potential contributions that medial interpretation can make to the field of RHM. By combining the presentation of our analytical concepts with interpreters’ dialogue, we aim to highlight the many possibilities for further considering medical interpretation within RHM. In the section that follows, we describe how we conducted interviews and focus groups to discuss the intricacies of translation in healthcare contexts with medical interpreters.

Co-Constructing RHM Research with Medical Interpreters

In order to compose this dialogue piece through the voices and experiences of medical interpreters, we interviewed medical interpreters who work in various hospitals in the Grand Rapids, Michigan area. In addition to these individual interviews, we held two small focus groups where interpreters collectively discussed their approaches to medical interpretation in their community. During both the interviews and focus groups, we introduced the concept of rhetoric, briefly discussed the field of RHM, and introduced the RHM journal as a potential venue for our conversation. Through these conversations, we sought to better understand how medical interpreters perceive their role in healthcare within their communities, giving interpreters the opportunity to speak back to some of the concepts and ideas that we have been researching in RHM.

The medical interpreters interviewed for this project were trained by and work in the Language Services Department at the Hispanic Center of Western Michigan. The Hispanic Center of Western Michigan is a nonprofit organization located in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The purpose of this organization is to provide access, education, and resources to the Latinx community in West Michigan and beyond (www.hispanic-center.org). Although the Hispanic Center provides a range of free services for the Latinx community in Michigan, the Language Services Department located inside the Hispanic Center is a for-profit translation and interpretation business that provides translation and interpretation resources for other communities in languages other than Spanish, including Arabic, French, and multiple indigenous languages from Central and South America. All of the revenue earned in the Language Services Department is re-invested in the Hispanic Center, fueling various programs for the larger organization. In this way, the Language Services Department at the Hispanic Center works under the same institutional constraints as a nonprofit organization, while simultaneously charging a small fee for services that is then re-invested into the community (see Gonzales & Turner, 2017).

The Language Services Department employs 30 bilingual and multilingual translators and interpreters who facilitate communication between community members and over 50 local service and government organizations in the City of Grand Rapids (e.g., the local police department, Child Protective Services, technology businesses, local museums, other nonprofit organizations). For the purposes of this study, we interviewed interpreters who work specifically in medical and healthcare contexts, facilitating conversations between patients and healthcare providers at several regional hospitals and healthcare centers. Below we present excerpts from our focus group and interview conversations, more of which you can access by following the video link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p51H0qkxy94. We also present, in a different font, some of our later considerations and observations about the conversations.

A Conversation with Medical Interpreters at the Hispanic Center of Western Michigan

In the following sections, we summarize our conversations about rhetoric and interpretation with medical interpreters. Through these conversations, we illustrate how medical interpreters theorize and practice rhetoric in their daily work, negotiating issues of language, power, and agency in healthcare interactions as they facilitate communication between patients and healthcare providers. As this conversation demonstrates, medical interpreters are intricately aware of their positionality as the professional “in-between” the healthcare provider and the patient, resulting in the added exigence to appease several stakeholders and audiences simultaneously through their rhetorical labor. As RHM readers engage with the dialogue below, we hope they continue to note the various ways in which disciplinary concepts like rhetoric are recognized and applied in multilingual healthcare interactions.

September 17–18, 2017, Grand Rapids, Michigan

Laura: The journal that we’ve been asked to write this article for, with your help, thankfully, is called The Rhetoric of Health & Medicine, and rhetoric is kind of what we study in school and what we study as researchers. Rhetoric has a bunch of different definitions. The idea, the sort of argument that we’re trying to make is that people who are medical interpreters and interpreters more broadly, use rhetoric. And what that means is just simply like you have to talk to different audiences. Every situation, although you might have training, of course, every situation, every interpretation and session that you go to is different. You walk in, and from the minute you walk in, you have to acknowledge all of the different factors, right? What the healthcare practitioner is doing, what the patient is doing, where you are. Sometimes you might do interpretation over the phone, which puts a whole bunch of different scenarios into play, right? And you, as a person, who’s trying to facilitate this communication, you use rhetoric to clarify a lot of times when something might not be super clear.

Rachel: Also, part of this emerging field of rhetoric of health and medicine is saying that inherently in all health and medical contexts, there are rhetorical things, even if it’s just providers trying to persuade people to live healthier lives, or patients trying to persuade their provider that they have something wrong with them. In those little interactions that we have, there’s the ways that we make appeals to different people in different ways. So, we are coming in to sort of remind people who are studying rhetoric of health and medicine that if you’re saying that, that means that multilingual contexts, and contexts with interpreters are also a part of this and a part of what we should be considering with those conversations.

Laura: So, we wanted to ask you: what is the rhetoric that healthcare interpreters use? How would you say healthcare interpreters use rhetoric, if at all? If you think it’s something completely different, then maybe elaborate on that.

John: In the medical setting, for me, the roadblocks that I have run into have been with the register. If you have a highly educated doctor who’s talking to a patient that has never learned how to read or write, and their level of physiological understanding is limited.… That’s one of the things that I try to encourage providers to understand is that some things just need to be explained. Whether or not I understand it, as an interpreter, is not gonna help because it’s not our role to explain. It’s our role to be the bridge of information. So, if we clarify, if we ask the doctor to clarify, or the nurse, or whoever is speaking over the head of this person who is listening, that’s a strategy that, you know, we use pretty frequently. Sometimes providers get angry and say, “Well you’re an interpreter, explain it to them. I don’t have time for this.” and I’d respond “Whose patient is it? Is it my patient? No, he’s your patient.”

So, one of the persuasive arguments that I give doctors is that, you’re the professional and I’m your assistant. I’m here to let him know every word you say. And I try to emphasize the fact that the doctor’s way up here and everyone else is way down here, and then that usually softens them up and they’ll explain. But, sometimes it takes persuasion, and that’s one of the things that you wouldn’t think you would have to do in this job, but there’s just such a wide misunderstanding of what interpreters really do that that’s necessary.

Betty: That’s the thing about being an interpreter is that you have that card under your sleeve that you can be a mediator for when the situation is getting like out of control, or out of the patient’s understanding. Because as an interpreter, we have to interpret everything that is said, but we have permission to intervene when we see that we are getting nowhere [laughs], which is different than being an advocate. You have permission to intervene as an advocate when the health or the safety of the patient is at risk. Another situation with language and communication, which goes both ways, the sayings that you guys have here, or the ones that we have down there. Sometimes you have to intervene as a cultural broker to say, “You know what? It’s just that in our country, this is used for this or we used to say this.”

I recognize what Betty is saying here as identifying the specific roles that interpreters learn about in interpreter training. Clearly identifying when and how often (or not) it is okay to intervene versus advocate is important in training professional interpreters. She also helps us transition into the conversation that happened around interpretation being more than just transfer of language. These are important considerations for RHM researchers who may be interested in working with practitioners who take on several different roles for different stakeholders in healthcare interactions. (Rachel)

LANGUAGE AND CULTURE

Through our conversations with medical interpreters, we came to understand how elements of interpretation and language accessibility often stem beyond the use of words in different languages. Medical interpretation requires an acute awareness and navigation of embodied and cultural competencies, elements that are only increasingly important in the work of RHM. (Laura and Rachel)

Rachel: A lot of people have very simplified ideas of what translation is: it’s from one language to another. And you all know that there’s a lot more complexity to that. So even just naming some of those things that we do because it’s complex because you know your audience is a complex language user, whether that’s the provider or the patient …

Mary: Interpretation and translation is more than just words. You have to deal with the culture and with the person and be able to put yourself in another person’s shoes.

Jaylyn: I find that jokes don’t translate very well.

Betty: Yes.

John: Oh, sure.

Jaylyn: Sometimes we use humor in healthcare to ease tension and stuff and sometimes it’s like Oh, oh …

Rachel: Can you think of an example?

Jaylyn: I feel like it’s happened a handful of times …

Betty: Well, it happened to me once when they were asking the patient, “How’s your cough?” “How did you spend the night?” or “How was your night?” and the patient would be like, “Yes, it’s a lot better it’s just that this darn … dog cough.” So the provider is like, “Cough dog? Dog Cough? How do you …?” [Laughs] So, I had to intervene there and say, “Well, in Mexico we call it this dog cough when it’s a very bad cough that is dry and it is strong and it hurts you when you cough and it’s like a bulldog kind of cough.”

Laura: What’s the phrase in Spanish?

Betty: Esta tos perra.

Alex: It’s good to have some cultural knowledge of the different, you know Latin community, because not everybody who speaks Spanish have the same concept of a word. For example, if I’m at the hospital and I’m with a person from Chile, and they just had a baby, then they’re gonna be like, “Oh, que bonita la guagua!” [Tr. Oh, what a beautiful baby!] They’re gonna be calling the baby guagua. For me, I’m from the Dominican Republic, that means a bus. So, I’m aware of the culture. Cause if I’m interpreting for the doctor, I can’t say, “Oh, what a beautiful bus.” You know? But I’m aware of what the culture is, where are they from, and things like that, so I can adjust.… It’s good to learn the different ways that we communicate.

While these examples demonstrated cultural brokering with phrases to describe symptoms for patients, interpreters also mentioned issues with medical terminology. This was particularly interesting for me in thinking about the concept of translation moments, considering how medical interpreters have to make immediate, high-stakes decisions as they choose which words to use in both the target and source language(s) during a consultation or procedure. (Laura)

Apoul: My experience is always with operations, like preparing the patient room before they go into surgery. I had one patient, it just came to my head right now, she had pregnancy—one in her uterus and the one optic [Rachel: I think she means ectopic], and then they thought it was in her fallopian tube, so that had to be removed. And the terminology [laughs] for that, God knows, it was the longest thing I ever heard when the nurse came and said it. Because I was like, “What are you here for?” She kinda explained it to me, you know, “I had an optic pregnancy and they will remove my tube today.” But when it was said in the medical terminology, that was the longest thing I ever heard [laughs]. I couldn’t even know how to say it back. So, it’s a good thing sometimes ‘cause I will ask my coordinator, “What is the surgery for?” to kinda prepare myself for the terminology ‘cause there is no way you’re gonna know everything in the book. It’s a field that we learn things every day, so you gotta prepare yourself.

Laura: What did you end up doing in that instance where there were these big words?

Apoul: I kind of knew already because she explained it in Arabic, so I said exactly what she said, “They’re removing the fallopian tube.” But when she said the medical word for it, if I didn’t know what I was walking into …’cause when they send in the need for the interpreters, they might not explain exactly what is being done. Even when you can ask the coordinators, “What am I walking into, what kind of surgery is it?” They’ll be like, “Oh they didn’t say.”

John: I had a similar situation about a year ago, and I was looking for the word … The nurse came into the room and told the patient, “Okay, we’re going to do such-and-such a test on your blood to rule out something.” And I can’t remember for the life of me what that word was because I had never heard it before in the 12 or 13 years I had been interpreting. I haven’t heard it since, but it was a term that I just had to tell the nurse, “I, the interpreter, am not familiar with that term, if you could give me a second to look it up.” And I luckily had a smartphone hooked up to WiFi.

Whether these interpreters took a pause to clarify what was being said or to look up a definition to be sure they were interpreting the meaning accurately, translation moments were present across various issues of language and culture. These instances represent a moment in time that can be analyzed for rhetorical decision-making. In these moments, the interpreters recognized the need to think creatively with their own language resources or turn to other resources (the patient, provider, or technology) to explain and inform subsequent meaning-making in the translation space. As these moments are memorable and common for interpreters, they often will inform how the interpreters approach future translation moments in translation spaces by identifying language variation, cultural differences, or technical terms that they have become more familiar with from past interactions and learning. (Laura and Rachel)

INTERPRETING AS ADVOCATING FOR THE COMMUNITY

Although frameworks like translation moments and translation spaces allow us to analyze the processes of language transformation in healthcare settings, our conversations also revealed that interpreters’ own histories and lived experiences often play an important role in both the strategies used during interpretation and the motivations for entering and continuing to partake in medical interpretation work. As RHM researchers continue working with practitioners to understand healthcare practices, we think that continuing to incorporate the stories of healthcare practitioners into our research can provide an added layer of depth and rigor in our scholarship. (Laura and Rachel)

Rachel: Tell us about why you decided to become an interpreter.

Alex: I came to the states when I was 14. I’m not familiar with the culture, with the language, even with the food. And people assumed that I knew English. They used to talk to me and I was just blank—with a blank face. People used to call me stupid and dumb and things like that. And I grew up trying to learn English. I wanted to learn English because I wanted to prove that I was smart, but it was hard because it doesn’t come that easy. It took me five years just to understand, and then it took me another five years when I finally moved to Michigan to start, like talking.… I was like, you know what, there is a lot of people that go through this and I think I can help ’cause I can relate to them.

John: Once I had been getting to know people here in the United States and traveling to Mexico … acquaintances would ask me, “Will you go to the Secretary of State with me? I have to fight a ticket or … will you go to help me buy a car? Will you help me go here or there to communicate with … you know, to work the system?” … And to not lose a license or whatever.

There was a lot of need, and the more and more people asked me, the more and more I found out that there’s actually a career choice as an interpreter, which I was not really aware of. So then people, friends, would funnel me into interpreting, and that’s pretty much where it all began for me … the need for the community.

Rawa: I became an interpreter when there was a need for the new refugees when they came into the country from the Middle East, Iraq. A lot of refugees that come from our country, they get here and … [it’s] just a different environment to them. To be able to communicate, it was difficult, and same as what he said (John), that they would ask me for help, “Let’s just do this—can you help us with this? Can you help us with going to a doctor appointment? Can you help us …”

I would be on the phone for a long time just trying to interpret for them or translate things for them. So I thought, okay you know what? Let me look up where can I find a job for that? And here we go, actually after a while, I opened my own agency that I have over 86 languages that we distribute for interpreters. It’s a beautiful thing to do. It’s not just the need of a job—it’s more than that. It’s those people from your own country trying to know about their health correctly.

Apoul: Pretty much my experience is like Rawa’s, like she said. I always had the passion. I learned English in middle school, so when I came to the U.S., I kinda knew how to speak it a little bit and nobody ever interpreted for me because I just worked my way into society and everything. But I know the struggles of learning a new language. It’s not as easy as it seems, and we all know that. But coming here and being in Michigan, as refugees coming a lot, there was needs and demands in my community as people had a language barrier. And they would ask you for numerous things like, “Help me out with this, can you read this letter for me?”

You were there to help them because you know that they cannot speak and you know, being a mediator, but nobody’s paying you. It kind of started early on because we help a lot of the people that we know—[even] til today. But everything kind of fell into place after being out here and knowing that it could be a career, and it fell into place after being out here and helping all the people. People were like, “Why don’t you be an interpreter? Why don’t you take it serious? Like, you know, develop it and get more skills and you can be certified by doing it.” So that’s how it happened, step by step.

Implications and Applications

The brief video montage linked here serves to wrap up our dialogue with the interpreters in addressing cultural, linguistic, and technical factors that they consider and navigate in their professional work: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p51H0qkxy94.

As the video montage demonstrates, the medical interpreters that we interviewed describe their roles in their community in many different ways. What we hope is most evident in the video is the many different rhetorical contexts that medical interpreters are constantly navigating as they negotiate issues of culture, language, and health simultaneously through their daily work. Medical interpreters are consistently working within translation spaces, and they encounter translation moments to various degrees as they make rhetorical decisions in their translation processes. Through these conversations with the interpreters, we hope their accounts show how they navigate language and culture in their daily work and demonstrate how medical interpretation can continue to shape the ways RHM envisions rhetoric and health intertwining with issues of culture and advocacy in healthcare contexts. Furthermore, we hope our dialogue extends the following applications for RHM researchers who can continue to honor the work of multilingual communities by:

Conclusion

Having the opportunity to discuss medical interpretation with the practitioners depicted in this dialogue helped us further understand all the moving parts that medical interpreters have to navigate in their everyday practices—as they decide which words to use for specific communities, as they move between units in a hospital to interact with patients and providers, and as they negotiate the affordances and limitations of their work with doctors, patients, and hospital staff. Through our conversations, medical interpreters continued to demonstrate how they negotiate issues of health, culture, and language simultaneously in their work, helping us continue to think of ways that we can advocate for the work of medical interpreters in RHM. During any interpretation session (i.e., translation space), rhetoric guides the multilingual verbal interactions as well as the embodied and material spaces in which these interactions take place. Thus, as we continue thinking about the role of medical interpretation within RHM, we hope to continue building on and highlighting the skills of medical interpreters as central, rather than merely tangential, to the work of our field.

Our notions of rhetoric, and RHM, will become more dynamic if we conceptualize rhetoric as something more than English-only communication. This seems to be addressed and acknowledged as an inherent aspect of rhetorical study, but much of our work continues to focus on healthcare systems that are multilingual and multicultural spaces without diving deep into those linguistic and cultural concerns, except with a focus on specific patient populations. If we, as researchers or practitioners, are limited in our own languaging abilities, then we need to reach out to others who can help add to our collective linguistic resources and collaborate in dialogue across contexts to further enrich our research questions, findings, and practical implications for the practices of healthcare today.

While we want to encourage all RHM researchers to consider how their work might engage multilingual concerns and medical interpreters more, we also want to note a few caveats. First, one of the most natural ways we can successfully pursue this is by recognizing those within our field—current and future scholars and teachers who reflect and are intimately familiar with the cultural and linguistic diversity of the potential patients we might want to work with or study. Rather than assume our call is recommending those who see themselves as monolingual to take on all of this on their own, we strongly encourage those researchers to consider how they might reach out to or collaborate with others who can bring those unique skills and perspectives to explore this work together. This will enhance the research but also the community of scholars studying RHM. While doing this, we must take care not to burden our collaborators or research participants by asking them to take on all of the intensive work that comes with taking care of the language issues at hand. For this project, Laura ensured that the interpreters and translators who participated would be paid their hourly wage for the time they spent with us. This is crucial if we want to be just, caring, and compassionate toward individuals who help us advance our own personal and professional agendas.

Pursuing RHM work in multilingual spaces can enrich so much of what we can learn from each other and from practitioners of health and language. Medical interpreters and the work that they do represent one way into this kind of work because they represent the “bridge” between linguistic and cultural realms of health and illness. We hope this can spur innovative ideas about how every area of RHM might potentially connect with medical interpreters and/or multilingual inquiry into the rhetorical moments of language use about health. Whether the topic is diabetes, vaccination, preventative screening, emergency medical services, or something else, there are always patients with limited proficiency in English who are experiencing these issues and who are attempting to communicate and respond to communication within healthcare systems focused on these concerns. Opening our eyes to the multilingual nature that is inherent in healthcare and RHM can lead to more comprehensive research, more culturally aware teaching, and hopefully, more success in caring for all patients and providers who navigate the messy moments of health and illness today.

LAURA GONZALES is an assistant professor of Rhetoric and Writing Studies at The University of Texas at El Paso. Her research highlights how multilingual communicators navigate translation across contexts. She is the author of the forthcoming monograph, Sites of Translation: What Multilinguals Can Teach Us About Digital Writing and Rhetoric.

RACHEL BLOOM-POJAR is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She studies rhetoric and writing at the intersections of culture, race, language, and health, with a specific focus on transnational healthcare programs, translation practices, and Caribbean Spanish.

References

Agboka, Godwin. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 28–49.

Batova, Tatiana. (2010). Writing for the participants of international clinical trials: Law, ethics, and culture. Technical Communication, 57(3), 266–281.

Bloom-Pojar, Rachel. (2018). Translanguaging outside the academy: Negotiating rhetoric and healthcare in the Spanish Caribbean. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Center for Immigration Studies. (2016). Nearly 65 million U.S. residents spoke a foreign language at home in 2015. Retrieved from https://cis.org/Report/Nearly-65-Million-US-Residents-Spoke-Foreign-Language-Home-2015

Ding, Huiling. (2014). Rhetoric of a global epidemic: Transcultural communication about SARS. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Gonzales, Laura. (forthcoming 2018). Sites of translation: What multilinguals can teach us about digital writing and rhetoric. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Gonzales, Laura, & Turner, Heather Noel. (2017). Converging fields, expanding outcomes: Technical communication, translation, and design at a non-profit organization. Technical Communication, 64(2), 126–140.

Meloncon, Lisa. (2017). Patient experience design: Expanding usability methodologies for healthcare. Communication Design Quarterly, 5(2), 19–28.

Meloncon, Lisa & Scott, J. Blake (Eds.). (2018). Methodologies for the rhetoric of health & medicine. New York: Routledge.

Rose, Emma J., Racadio, Robert, Wong, Kalen, Nguyen, Shally, Kim, Jee & Zahler, Abbie. (2017). Community-based user experience: Evaluating the usability of health insurance information with immigrant patients. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 60(2), 214–231.

Segal, Judy Z. (2005). Health and the rhetoric of medicine. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

St.Amant, Kirk. (2015). Aspects of access: Considerations for creating health and medical content for international audiences. Communication Design Quarterly, 3(3), 7–11.

St.Amant, Kirk. (2017). The cultural context of care in international communication design: A heuristic for addressing usability in international health and medical communication. Communication Design Quarterly, 5(2), 62–70.

St. Germaine-McDaniel, Nicole. (2010). Technical communication in the health fields: Executive Order 13166 and its impact on translation and localization. Technical Communication, 57(3), 251–265.

Sun, Huatong. (2012). Cross-cultural technology design: Creating culture-sensitive technology for local users. New York: Oxford University Press.

1 Although we use the term “Limited English Proficiency (LEP)” in this piece to align with terminology used in U.S. government documents, we acknowledge that this term is problematic in that it can suggest patients who identify with heritage languages other than English have literacy limitations. As we demonstrate in this dialogue, we hope to continue flipping this deficit model toward language difference in healthcare.